The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece

by Marguerite Rigoglioso, Ph.D.

Greek religion is filled with strange sexual artifacts –– stories of mortal women’s couplings with gods; rituals like the basilinna’s “marriage” to Dionysus; beliefs in the impregnating power of snakes and deities; the unusual birth stories of Pythagoras, Plato, and Alexander; and more. In this provocative study, Marguerite Rigoglioso suggests such details are remnants of an early Greek cult of divine birth, not unlike that of Egypt. Scouring myth, legend, and history from a female-oriented perspective, she argues that many in the highest echelons of Greek civilization believed non-ordinary conception was the only means possible of bringing forth individuals who could serve as true leaders, and that special cadres of virgin priestesses were dedicated to this practice.

Greek religion is filled with strange sexual artifacts –– stories of mortal women’s couplings with gods; rituals like the basilinna’s “marriage” to Dionysus; beliefs in the impregnating power of snakes and deities; the unusual birth stories of Pythagoras, Plato, and Alexander; and more. In this provocative study, Marguerite Rigoglioso suggests such details are remnants of an early Greek cult of divine birth, not unlike that of Egypt. Scouring myth, legend, and history from a female-oriented perspective, she argues that many in the highest echelons of Greek civilization believed non-ordinary conception was the only means possible of bringing forth individuals who could serve as true leaders, and that special cadres of virgin priestesses were dedicated to this practice.

Her book adds a unique perspective to our understanding of antiquity, and has significant implications for the study of Christianity and other religions in which divine birth claims are central. The book’s stunning insights provide fascinating reading for those interested in female-inclusive approaches to ancient religion.

Purchase the book at:

Reviews

“The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece is bold, creative, and courageous, and makes a considerable contribution to feminist re-readings and reinterpretations of religious and mythological traditions from the Greco-Roman world. Especially convincing is the close reading of a large collection of mythological texts that illustrate the subtle and not-so-subtle movements from a more matriarchal to a more patriarchal ethos.”

–– Marvin Meyer, Ph.D., Griset Professor of Bible and Christian Studies, Chapman University; author of The Gospel of Judas, The Gospels of Mary, The Gnostic Bible, Ancient Christian Magic, and other volumes

“With this pioneering work, Marguerite Rigoglioso has illuminated the coherence and the centrality of the seemingly disparate references to divine parthenogenetic birth in Greek religion. Her insightful study of the priestesshoods of divine birth brings the subject into focus and suggests new scholarly perspectives.”

–– Charlene Spretnak, author of Lost Goddesses of Early Greece

“Thought provoking and superbly written, this is the only book to examine thoroughly and seriously the question of divine birth in ancient Greece. Rigoglioso meticulously builds her bold thesis of the existence of early divine birth priesthoods, integrating vast amounts of data and resolving paradoxes previously unexplained in the literature. Imperative for classical scholars, the book provides stunning insights that should be a fascinating read for anyone who has even the slightest interest in spirituality, religion, feminism, or ancient history.”

–– Jorge N. Ferrer, Ph.D., coeditor of The Participatory Turn: Spirituality, Mysticism, Religious Studies

“Marguerite Rigoglioso is a unique scholar who has skillfully woven an important study that shifts the dominant gaze on pre-Christian origins. Her work allows for a more holistic perspective regarding a major religious belief of the world––that of virgin birth. What a treasure––an original and scrupulous scholar who writes well and suffuses her study of myths

with passion!”

–– Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum, Ph.D., author of Black Madonnas: Feminism, Religion, and Politics in Italy

Review in Facing North

~review by Michelle Mueller:

http://facingnorth.net/Womens-Interest/the-cult-of-divine-birth-in-ancient-greece.html

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: A Taxonomy of Divine Birth Priestesshoods

Chapter 2: Divinity, Birth, and Virginity: The Greek Worldview

Chapter 3: Athena’s Divine Birth Priestesshood

Chapter 4: Artemis’s Divine Birth Priestesshood

Chapter 5: Hera’s Divine Birth Priestesshood

Chapter 6: The Divine Birth Priestesshood at Dodona

Chapter 7: The Divine Birth Priestesshood at Delphi

Chapter 8: Is Virgin Birth Possible? and Other Outrageous Questions

Notes

References

Index

Excerpt

From the Introduction of The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece:

Were holy women of ancient Greece once engaged in attempting to conceive children miraculously? . . . . [S]hards of a Greek history seeming to link women and divine birth have continuously presented themselves to me, glinting through obscure passages in ancient texts and in the prose of unsuspecting contemporary scholars. I have collected these pieces, and in this book I have assembled them. The result is a vessel that may still have many missing parts, but one that begins to reveal an integral form and shape, nonetheless.

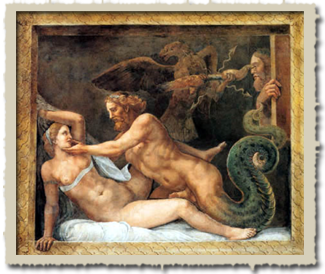

During the course of this research I have come to realize there have been so many artifacts staring at us for 2,000 years, in fact, that it is truly stunning no one has put them together before as evidence of possible female cultic practice. Practically all of the legendary heroes who came to head the great genealogical tribes of early Greece, as well as various historical political and spiritual leaders and a handful of humans turned divine, were said to have been born of mortal women through sexual union with gods. Not only were Heracles, Perseus, Theseus, and a host of other legendary heroes associated with divine birth stories, but so were historical figures such as Pythagoras, Plato, and Alexander the Great.

During the course of this research I have come to realize there have been so many artifacts staring at us for 2,000 years, in fact, that it is truly stunning no one has put them together before as evidence of possible female cultic practice. Practically all of the legendary heroes who came to head the great genealogical tribes of early Greece, as well as various historical political and spiritual leaders and a handful of humans turned divine, were said to have been born of mortal women through sexual union with gods. Not only were Heracles, Perseus, Theseus, and a host of other legendary heroes associated with divine birth stories, but so were historical figures such as Pythagoras, Plato, and Alexander the Great.

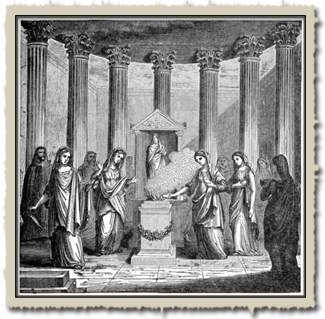

In certain corners of the Graeco-Roman world, it was believed that miraculous conception could occur through the influence of snakes and celestial rays of light. The healing cult of Asclepius held that women could be impregnated with supernatural assistance—a belief that was the basis for the entire nearby Egyptian civilization. The basilinna, the “queen archon” of classical Athens, was even attested to conduct a secret and presumably sexual rite with the god Dionysus every year. Are such stories and practices—and many, many more—to be dismissed as mere remnants of mythology—that is, fiction—alone? Or do they point to something important about the actual beliefs and rites of ancient Greece? . . . .

In Chapters 6 and 7, this book draws together interesting or typically overlooked details regarding the oracles at Dodona and Delphi, particularly as they relate to women and the feminine. It provides a more comprehensive feminist analysis of the goddess Dione at Dodona, and of the female oracular functionaries at both sites, than has been attempted before. The discussion of the possible connection between these cultic locales and the astral realms of Taurus and the Pleiades opens the window to an expanded understanding of the significance of such star systems in Greek religion and of their relation to the feminine, as well as of prophetesses’ likely engagement with not only the chthonic but also the celestial mysteries.

In Chapters 6 and 7, this book draws together interesting or typically overlooked details regarding the oracles at Dodona and Delphi, particularly as they relate to women and the feminine. It provides a more comprehensive feminist analysis of the goddess Dione at Dodona, and of the female oracular functionaries at both sites, than has been attempted before. The discussion of the possible connection between these cultic locales and the astral realms of Taurus and the Pleiades opens the window to an expanded understanding of the significance of such star systems in Greek religion and of their relation to the feminine, as well as of prophetesses’ likely engagement with not only the chthonic but also the celestial mysteries.

In bringing to light the fact that the dove and the bee were symbols of divine birth, this book further explains why oracular priestesses at Dodona and Delphi were identified with such totems. Similarly, it renders plain why the lore of such places was replete with stories of virgin birth. It explicates the Delphic Pythia’s “spousal” relationship with Apollo and, by elucidating the dual understanding of the concept of “conception” as both a physical and mental/oracular process, makes clear why the same verb, anaireô, “to take up,” would have meant both “to give an oracle” and “to conceive in the womb.” In so doing, this book provides a coherent rationale as to why oracular and parthenogenetic aspirations would have been understood as the province, in many cases, of prophetesses. In its thesis that terms such as parthenos (variously but unsuccessfully defined by classics scholars as “maiden” or “virgin”) as well as heroine and nymph were titles originally used to denote the priestess of divine birth, articulated in Chapter 2, the theory detailed here allows for the resolution of contradictory meanings and characteristics associated with such words, and lends to a new interpretation of Homer’s “cave of the nymphs” as symbol of virgin birth. This book foregrounds the importance of virginity as a requirement in certain priestesshoods, as well, but clarifies that celibacy originally was a specialized practice, not a burden imposed on all young women with its later moral connotations. The theory likewise eases the apparent contradictions associated with the derivation of the Greek parthenos from the Egyptian name Pr thn, allowing for a conjectural definition of the term as the poetic and apt “holy vessel for the divine star being who has descended from the heavenly cow/Hathor/Neith.”

Marguerite Rigoglioso, The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece,

2011, Palgrave Macmillan, reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.

This extract has been taken from the author’s original manuscript and has not been edited.

The definitive version of this piece may be found in

The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece by Marguerite Rigoglioso,

which can be purchased from http://www.palgrave.com.

Text Copyright: Marguerite Rigoglioso

Have questions or want to inform me about mentions of parthenogenesis, divine birth, and The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece in the media? Contact my team here